Foreword

Contents

Foreword¶

The Rise of Micromobility¶

Like old-wine in new bottles, bicycle-sharing systems are nothing inherently new (Copenhagen City Bikes launched in 1995), but the world we find ourselves in is much different than what it was even just 20 years ago. Specifically, we live in a world with ever-increasing population-densifying cities; by 2050, most of humanity will be urban-dwellers. Consequently, the demands and expectations for what public transportation systems can handle are changing rapidly, for many different reasons. One can mention the unbearability of air pollution caused by congested traffic arteries, the political pressure for decision-makers to curb greenhouse gas emissions, the changing philosophies of urban planners towards liveable and walkable cities, and the prohibitive costs of car ownership, to name just a few. As such, a great deal of transportation pressure in urban spaces isn’t to primarily cover large distances, but in enabling pathways of micromobility to fill transportation gaps without massively transforming existing infrastructure, while attaining standards of environmental sustainability, and providing an affordable mode of transportation for both commuters and operators.

Micromobility is defined as mode of transportation which are fully or partially human-powered vehicles such as bikes or scooters operating at speeds under 25 km/h (15 mph).

Bikesharing, the shared use of bikes for individuals at publically available access points, is one prominent example of micromobility, and a rapidly growing industry accounting for 84 million trips in 2018, twice the number of trips compared to the previous year1. Its market-size was valued at USD 3.1 billion in 2018, with a forecasted compound annual growth rate of 17% as of 20202.

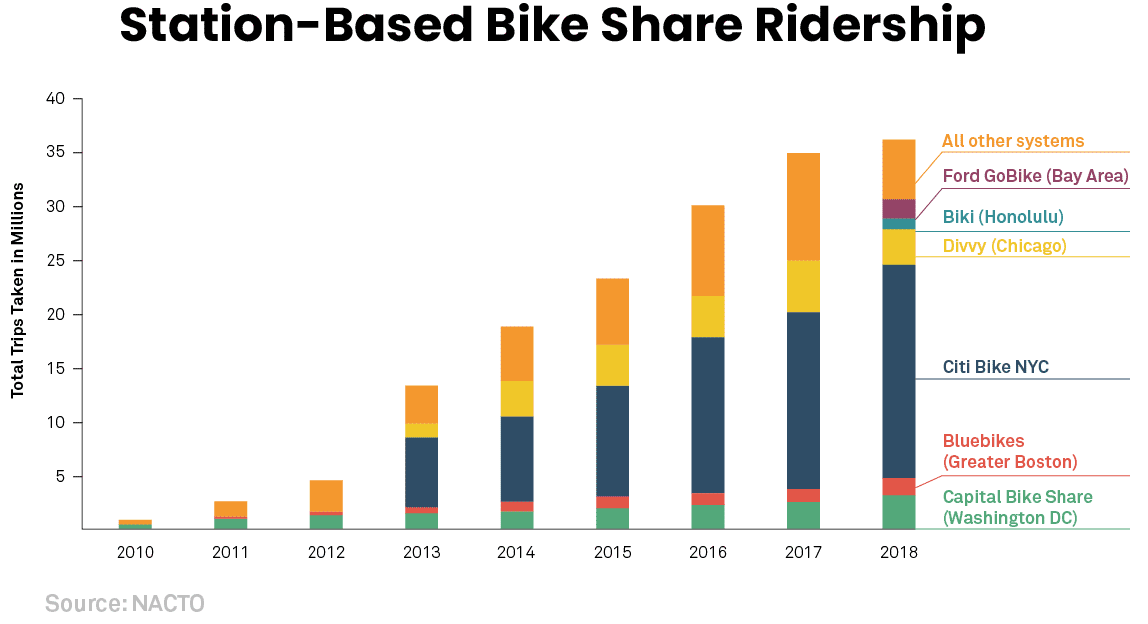

In the United States, bikesharing is predominant in large, densely populated cities such as New York City, which accounted for 40% of all bike trips in the country for 2017 alone3. Six cities accounted for 84% of all station-based (meaning that the bikes had to be returned to a docking station) bikesharing trips in 2018:

According to an INRIX Research study, micromobile commuting options such as bikes and scooters could replace nearly 50% of short-distance (< 3 miles) vehicle trips in the U.S.4. San Francisco, the focus of this project’s analysis, ranked 10th5 in INRIX’s ranking of U.S. cities with the greatest micromobility potential, an index based on facors including efficient and cost-effective travel, reduced traffic congestion, decreased emissions impact, and anticipated effects on the local economy.

For a comprehensive overview of the main players in the micromobility industry, consult the diagram below by Micromobility Industries (hover over the image for a zoomed-in view to the right).

Bikesharing: A Tenuous Affair¶

Bikesharing systems tend to be public-private partnerships, with ridesharing companies like Lyft and Uber involved in the micromobility market, seeking to set the tone for the industry. Uber’s strategy, for instance, is to build and own the urban transportation’s ecosystem within its app delivery service, providing an array of ridesharing transportation options including electric scooters and bikes6. However these partnerships are politically liable to controversy and pushback, as they are signifiers of the prevailing trend of the privatization of public commons and services.

In San Francisco, Lyft’s Bay Wheels has seen backlash caused by unpopular rental pricing changes in 2020 and 2021. Horace Dediu, a leading analyst credited with coining the term “micromobility”, stated: “I see bikeshare systems as public transit that should be funded and looked upon as public transit, not as a standalone function that has to be in the black all the time to operate.”7.

Although the market of micromobility is still maturing, it remains to be seen how the industry will evolve with the disturbances of daily-life brought upon by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Paradigm Shift of Dockless E-Bikes¶

The formative model of bike-sharing was docked: rent a docked-bike at a pick-station, and drop-it off at the nearest drop-off station to your destination. Dockless bikes remove this barrier, since these bikes are not bounded to a station. This has the advantage of widening the scope of mobility for commuters, requiring just the app to geolocate and borrow the nearest bike. However this poses challenges for operators (in terms of durability, maintenance etc.) and cities, such as added clutter on sidewalks (an issue similar to the highly publicized roll-out of e-scooters, for instance).

Dockless bikes are designed for short, spontaneous trips, such as a commuter first-or-last mile option. They also present a much cheaper alternative to a potential bus trip or traditional bike share daily pricing scheme.

Learn more:

1: National Association of City Transportation Officials

2: VynZ Research

3: WIRED: Americans Are Falling in Love With Bike Share

4: INRIX Research: Managing Micromobilty to Success

5: INRIX Research: Shared Bikes and Scooters Could Replace Nearly 50 Percent of Downtown Vehicle Trips

6: WIRED: Uber’s New Bid for Dominance: Controlling Every Way You Move

7: CITYLAB: Lyft’s New E-Bike Aims to Conquer the Post-Pandemic City